Partly because I have the world’s worst sense of direction (cruel irony for a natural-born traveler) and partly because it’s just how I love to travel, I have no clue where I am. My daily routine while on this 90-day journey following a raindrop, is to have no routine, nor schedule, nor agenda. I follow any road that seems to beckon in any direction for any reason and often for no reason at all, trusting the GPS to find the way home at the end of the day. So, I don’t realize that I am heading into the small town of Leland, Mississippi, until I find myself on its main street – and I don’t remember having read about a small blues museum here until I see the sign, “Highway 61 Blues Museum,” which brings me to a stop.

The straw-hatted man leaning near the door having a smoke grins at me and nods, as if affirming that I have made the right choice. As I approach, he says something which I can’t quite catch, but he is clearly inviting me inside. He follows me in and introduces himself as Pat Thomas, son of the legendary blues man and folk artist James “Son” Thomas and takes me to the display case of his father’s memorabilia. He comes here several times a week, he says, just to see who might stop by. It takes my ear a few minutes to grow accustomed to his speech and his deep Mississippi accent, but it takes no time at all to understand his smile and his piercing hazel eyes.

Since I am the only guest in the museum, we settle onto stools and he begins to talk about his father and the music and art that they shared. He didn’t need to know how to read, he says, “cuz you cain’t learn it from no book nohow.” His father taught him to sculpt and to find the clay along the river banks and taught him to draw using any materials they could find. He learned to play the blues, he says, just by watching his father’s fingers.

“Daddy always tol’ me,” he says, “they’s lots o’ ways you can have the blues. If you broke, that’s the blues. If you hungry, that’s the blues. If you got a good woman and she quit ya, that ain’t nothin’ but the blues.” “Sometime I get a happy blues feelin’,” he says, “and sometime I get a mad blues feelin’. It just somethin’ that come in ya – ya gotta feel it.”

He gets very quiet when he talks about his father dying in 1993 and says that for a while he couldn’t play and “just hadda leave that guitar alone. But then,” he says, “I started feelin’ kinda shamefaced and I knowed I hadda put my heart there for my father.” Now, he mostly plays the old songs, just like his father did. “Sometimes,” he says, “I go to the graveyard and play and it seem like he kinda wakes up.” “But then,” he continues, “he just git back down in that hole o’ his.”

He takes up his guitar then and plays and sings for me and I know that I am hearing the “real Delta Blues” as it was heard on porches on sultry summer evenings. The simple, repeated lyrics tell of a love gone bad, but beneath that is a soul’s need to sing to sustain a body through a life of hard work and oppression. We can hear the stories, see photos and visit museums, but only those who lived it know what it was like to be black in a segregated South. This is the music of such souls.

It’s tough to describe Pat Thomas. He is some mixture of wisdom and innocence and keen perception. When he smiles, his whole face is transformed and when he laughs, his whole body participates; yet there is something more going on, something a little mysterious behind those hazel eyes.

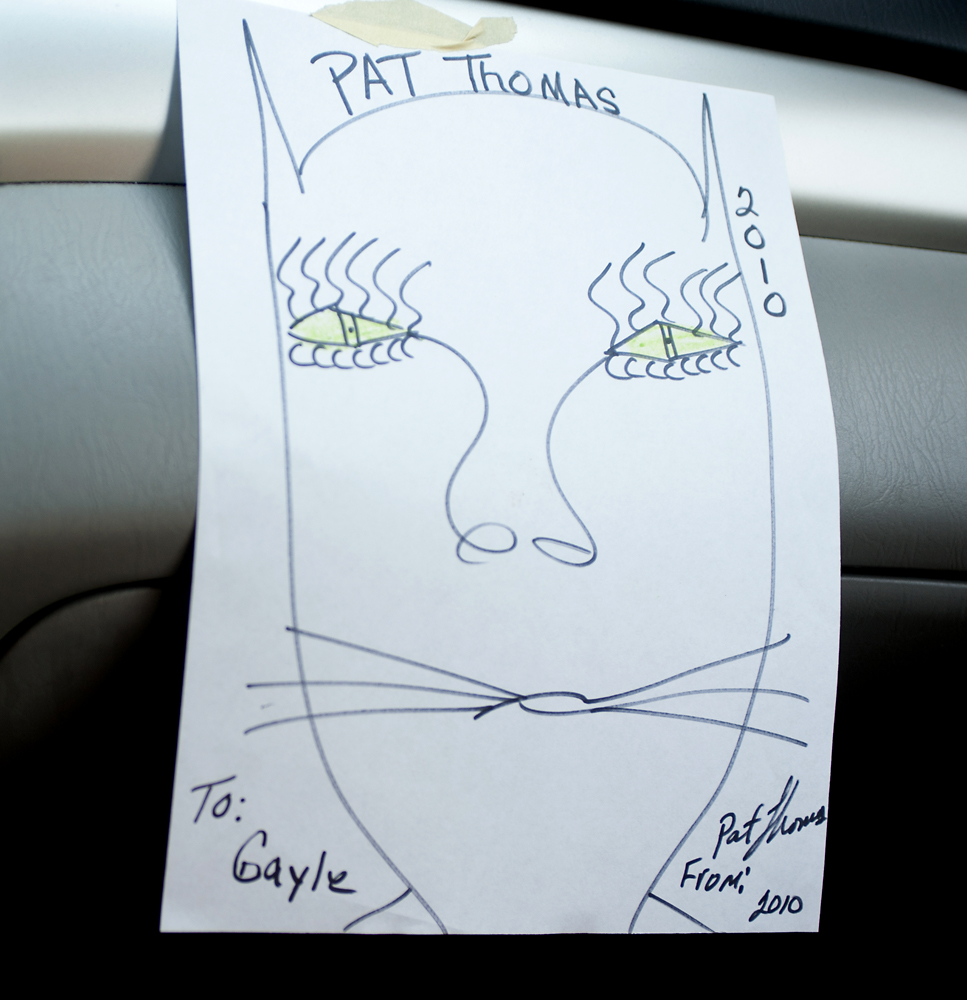

When it’s time to go, Pat draws a “diamond-eyed cat” for me and says to keep it with me for good luck. “It’s got hoodoo magic,” he says with no trace of a smile. I can’t say I understand much about hoodoo, only that it is different than voodoo and originated here in the Delta among slaves. When he hands me the drawing, however, and looks into my eyes, I get goosebumps. So, I tape my diamond-eyed cat to the dashboard and let it ride shotgun a while.

Click here Pat Thomas to hear a bit of him singing “Highway 61 “Blues”